Hello, my lovely owl friends! It is now well and truly fall in the northern hemisphere, but I keep thinking about our modern idea of the seasons. I read a wonderful book last month about medieval/Anglo-Saxon calendrical ideas, and I think I could really get behind the idea that there’s really just summer (March to September) and winter (September to March). Restore midsummer and midwinter to their proper place of importance! Allow fall and spring to just be part of the transition between the two big seasons, since they never last as long anyway! Something to consider, anyway.

Project Updates

Gryphons & Gargoyles Out Now

The third of the three games I wanted to release this year is available now! This one is Gryphons & Gargoyles, which started as a joke project where I took the very fake D&D-analog from the TV show Riverdale and turned it into a real game. Except then I got weirdly invested in it and ended up making it into a really good game despite the fact that I can’t actually charge money for it, because I refuse to decouple it from the source material. This has been such a kooky little project for me, but it has been a fun one! So that’s up on itchio and DTRPG now, for free! Check it out!

Announcing: Ink & Courage

So, I teased this a bit on bsky earlier in the month, but I’ve finally started working on a project I’ve wanted to do for years. Ink & Courage: Newsies on Strike is a game derived from The Price of Coal, using similar but not identical mechanics to put players into the 1899 New York City newsboy strike – the same subject as the wonderful musical Newsies. This will be an iteration of the game that is a bit more family-oriented, in terms of its tone and subject matter – not a kids game per se, but one you could (theoretically) play with middle schoolers (shoutout to everyone I know who’s run The Price of Coal for high schoolers, by the way, you rule).

It took me years to get around to this project, despite having it on a backburner that whole time, for a few reasons. First of all, in the immediate wake of The Price of Coal, I wanted to do something really different from it, because I hated the idea of being seen as a one-trick-pony. Like I didn’t want anyone to think that this particular style of play, this particular genre of game, was ALL I had in me, because it’s not! I make lots of different kinds of games! And now that there’s a few more of those out there with my name on them, I am less worried about only having this one type of thing to point to when people ask me what I do.

To be candid, I’ve actually basically reversed course on this worry, taking it all the way back around to “what if this is the ONLY thing people want from me and the only type of thing I do that might be successful?” Because, to be frank, most of my other stuff has not done well! This is largely attributable to the fact that I didn’t crowdfund them, but it doesn’t fully shut up the little voice in my head fretting that people just aren’t interested in other subject material or play styles from me, no matter what it is. I almost talked myself out of picking this project up, because it might feel really bad to have that confirmed! But I think that’s all putting the cart before the horse really, and sooner or later, you just have to make the damn game.

Another factor in the delay for Ink & Courage was a desire to make sure that this new game wasn’t just derivative, that it wasn’t just doing the same thing over again, and crucially – that I want it to be just as good, if not better than The Price of Coal. Five years is a long time to have improved at design and be better at articulating what my goals are and translating those goals into a finished game. Even if this type of game IS all that people want from me, I really strongly wanted Ink & Courage to be something that could stand on its own, something that couldn’t possibly just be seen as a cash-grab or a play for attention. And I think I’ve skilled up enough now that that’s possible.

Of course, with that (I like to think) increase in my ability, I have also picked up much bigger goals for the game. I really want this to serve as both an introduction to the mode of story gaming, something that will really ease people in who’ve never done it or anything like it before (compared to The Price of Coal, where I got away with some assumptions that people who found it would already be familiar with that style of play), AND as an introduction to the whole topic of labor rights, collective action, and why they’re important. And again, ideally doing both in a way that is suitable for a slightly younger audience, while still engaging to adults. So… that’s a lot! That’s a big goal!

So when I say I’m “announcing” this project, I think it will likely be a while before I can call it finished, even working from a pretty well-established foundation. But it’s something I’m really excited to finally be working on, and I hope people will be excited about it when it’s ready for you!

Other Thoughts

Procedurality

This month, I joined the discord server for the Unwritten Earths Symposium podcast from fellow game designers Epidiah Ravachol and Nathan D. Paoletta. Over there, I got the chance to jump in on a game of Swords Without Master, run by Eppy himself. SWM is a game that I’d read often but had never gotten the chance to play, so that was super exciting, and I had a really good time with it! It also was a play experience that clarified something that had been quietly brewing in the back of my mind for a while, without me even realizing it!

In SWM, if you’re unfamiliar with it, play shifts around through several distinct phases (the Rogues Phase, the Perilous Phase, the Discovery Phase, etc.), which each have somewhat different rules about who does what when (who says what, who rolls the dice and when, what the goals and stakes are, etc.). In play, this is pretty plainly spelled out – Eppy, as the Overplayer, would declare “we’re going to do a Discovery Phase”, in plain English. Within a phase, players would use key phrases linked to their actions – “Show us how you broke out of this prison once before!” as we pass the dice to that player, etc.

This isn’t the only game to use clearly delineated phases of play or to prompt players with specific language to use. Off the top of my head, I was thinking about the two campaigns of Agon I ran a few years ago, which has several distinct phases of play within a session, and Polaris: Chivalric Tragedy (another game that I have read over and over but haven’t had a chance to play yet! Someday!) uses a very limited set of key phrases to shape players’ negotiations over what happens in a scene.

But sometimes just playing something in a different context, or with different people, or a different formulation of mechanics, or just in a different frame of mind, brings you to a different conclusion as to how these things should be done.

Way back when I was running Agon, I tried it two different ways when I was running for two different groups – in the first of the two, I tried to NOT use the names of phases or to declare “okay, this is going to be the clash/threat/finale phase of battle”; I tried to allude more artfully to the fact that that was what was happening, I tried to make it all very fluid and immersive and not at all call attention to “we are playing a game right now”. In short, this was not a success! It made my players more confused than not! My aim was to reduce how “procedural” things felt, and previously I would have just said that I did not succeed at that aim. Now I’m not sure that was a good aim at all.

In the second of the two groups, I did use the game’s terminology, I did say “okay so we’re doing the clash phase here”, but I felt awkward and self-conscious about it and I think I went too far in the other direction in not doing ENOUGH description and scene-setting, and for reasons I hope unrelated to that, the game also just wasn’t really a hit with that group (it happens! Not every group clicks with every game! If they did, we wouldn’t have so many games!). One of the complaints was that it “felt too procedural”, and after kind of striking out running the game twice, I was prepared to accept that this just wasn’t something in my GMing skillset at that time.

I don’t accept that anymore! For one thing, I was aiming for a very particular kind of immersion that I don’t really believe in or experience myself as a player! I never know what people want when they say they want “immersive” games! Baby we’re a bunch of nerds sitting around a dining room table with a box of pencils and some index cards, what is immersive about this? So it actually isn’t a bad thing to have moments that “take everyone out of it” or “remind us we’re playing a game”. That’s good, even! I like playing games, and if I wanted to just do freeform RP, I’d do that instead.

(There’s a Wes Anderson quote I love from an interview about the very conscious artificiality of his films, where he says ‘If someone says ‘this takes me out of it,’ I tend to say ‘well, we’re doing it anyway.’” Hell yeah)

But also, watching Eppy run Swords Without Master, I think I got a really good glimpse of a fair balance between the two modes I had tried with Agon. He uses the game’s mechanical language – “let’s do a Rogues Phase now” – in a way that feels natural and precise, but without dwelling on it. I had read the rules before, but in play, I got to see how the Overplayer’s responsibility of describing the impending threat, the Thunder, helps smooth over that process, building a procedure that doesn’t feel clunky.

And there’s also just the realization of personal taste and preference that came in when I was able to experience a game as a player and not as a GM, where I had previously worried that my players’ preference for something less procedural was a failure on my part, even though I’d been having fun with both Agon games! Sometimes things can just be a difference of taste! But I’m so used to evaluating my own GMing experiences as “did I do a good job today?” that sometimes it helps to step back out of it and realize that maybe there was just a difference in taste between me and my players.

Of course, because I’m not just a player and a GM, I’m also a game designer, all of my play experiences end up filtering back into my design, in one way or another. I have previously avoided doing some things that might strike me as a bit more “procedural” in nature, for fear that they’ll land in a clumsy way, or that my own GMing style isn’t automatically suited to doing (one thing about designers – we have to make games that we like to run! Or else we get real unhappy with them real quick!), so it’ll be interesting to see if some of that creeps back in now.

And the moral of the story is: you should play lots of different games with lots of different people!

RPGs as Etiquette Manuals

Hey, speaking of games that use ritual phrases like magic words, have you ever thought about… manners? Etiquette? Politesse? This is a great segue.

When I was a weird little girl with an interest in history, I went through an obsession with old-school etiquette manuals. Comportment, etiquette, the formal rules of behavior – if you don’t know, these things used to be written down and formally taught, not just something you were supposed to intuit in unfamiliar situations. Sure, this goes for things that we’ll disregard as silly and irrelevant now, like “which fork to use for which course at a 12-course meal”. But it also goes for things that would have been broadly applicable as a kind of life-smoothing advice, just making every social situation go a little bit nicer for everyone.

When I bring up the idea of “an RPG book is like an etiquette manual”, along the lines I have seen other people say “an RPG book is like a cookbook”, I think I get misunderstood a lot, presumably because those people have not read actual etiquette manuals (fortunately, not everyone is a weird 9-year-old reading Emily Post’s 1922 opus). They either think I’m referring to regular daily good manners (although I do think, yes, we SHOULD be saying thank you to each other after every game! Thank you for playing with me!), or they think I’m in favor of imposing ritual key phrases as noted above (which I sometimes am! But not for every game, that’d be silly!). Or occasionally it’s taken as another framework for examining safety tools, which I think are part of this, but not all of it and not even the core of it (using safety tools is polite! It is not the only polite behavior!).

What an etiquette manual does is define a wide variety of situations a person might find herself in, and spell out for her (in a non-judgmental way) what are the acceptable modes of behavior in that situation. Behavior that is encouraged at a debutante ball is frowned upon at a funeral, and vice versa. It also often gives advice on recognizing different situations that might appear, on the surface, similar or the same – how IS the afternoon tea different from the luncheon, and how does that impact your behavior? What are your rules of engagement? How do you comport yourself to show respect for others and respect for yourself? How do you ensure that everyone around you is enjoying your company and how do you best enjoy theirs?

Etiquette is a form of social contract. It is an agreement as to how all participants will behave in a given social situation. Etiquette… is a magic circle. Those of you familiar with your theories of play will pick up what I’m putting down. Every different RPG is an etiquette manual for its own specific situation, and trying to apply the modes of behavior universally to every game is not necessarily going to give you great results, even if it did once before. It’s one thing for a young lady to wear white to a debutante ball, and another thing entirely for her to wear that same white dress to someone else’s wedding.

Some things ARE universal, or close to it – I like to think that “engaging with the premise in good faith” is the “please and thank you” of RPG play. This might be easier with some illustrative examples, so let’s take two RPGs I happen to already have open on my laptop (I’m really bad about closing tabs) and that I think a lot of you will already have as well – Apocalypse World (2e) and Wanderhome.

Apocalypse World is wonderful at spelling out how you, as a player or an MC, are supposed to engage in its situations of play. Under a big header labeled “SAY THIS FIRST AND OFTEN”, there is a broad guideline that will be a solid foundation for anything you might attempt in that space: “To the players: your job is to play your characters as though they were real people, in whatever circumstances they find themselves—cool, competent, dangerous people, larger than life, but real. My job as MC is to treat your characters as though they were real people too, and to act as though Apocalypse World were real.” Whenever your intuition fails you, this thought should be reiterated. This is your “etiquette 101” of Apocalypse World. This is the agreement we’re all making about how to behave here. When in doubt, it’s hard to go wrong in Apocalypse World if you follow this rule, just like it’s hard to go wrong turning your phone off in the movie theater (no, for real, put your phone away in the movie theater).

That’s a really solid, obvious way of spelling things out, and I personally like obviousness when it comes to defining how it’s appropriate or inappropriate to engage in a situation. But that’s not to say that more subtle or lengthier ways of explaining this aren’t valid. In Wanderhome, there’s a section titled “Our Journey”, which explains why this game isn’t about traditionally “satisfying” narrative structures and doesn’t embrace them, but instead embraces dropped threads and contradictions and uncertainty and speculation that you may never know the real truth of (in the annotated version, Jay also notes that this section was originally much longer, and specifically suggests that people more used to Apocalypse-World-style play might struggle with this type of play!). It doesn’t give a lot of hard and fast rules or examples of what that looks like, but broadly asks you to be open to figuring it out.

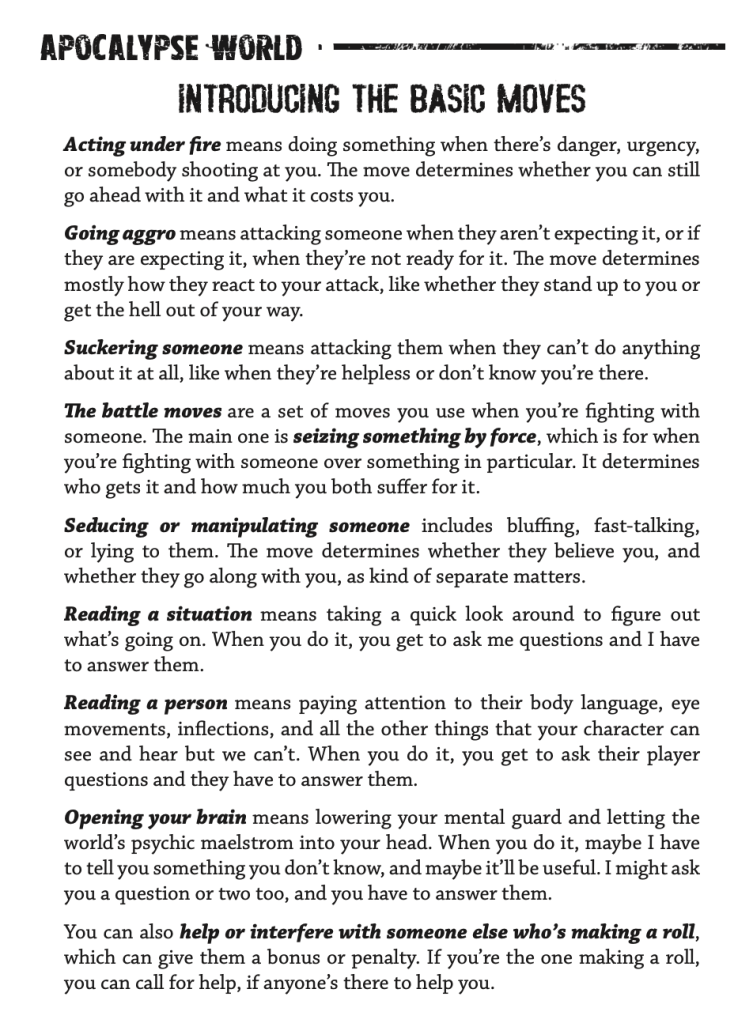

In more specific situations, things that aren’t covered by your etiquette 101, your pleases and thank yous, the games’ mechanics step in to tell you how it’s appropriate and expected for you to behave. Apocalypse World does this with its basic moves. You don’t HAVE to do any given basic move, and not every move will be applicable to every situation, but within the scope of play, you should expect situations to arise where these ARE the appropriate responses and where you SHOULD feel encouraged to do them. You won’t always want to “go aggro” or “seduce or manipulate someone”, but everyone should expect those to be on the table as acceptable and encouraged modes of engagement. I don’t have to accept the man asking me to dance, but I also shouldn’t be weirded-out and out-of-sorts that a man is asking women to dance at a ball. I knew that was on the table and accepted that by coming to the ball in the first place, even if I personally came to play bridge with the old spinsters.

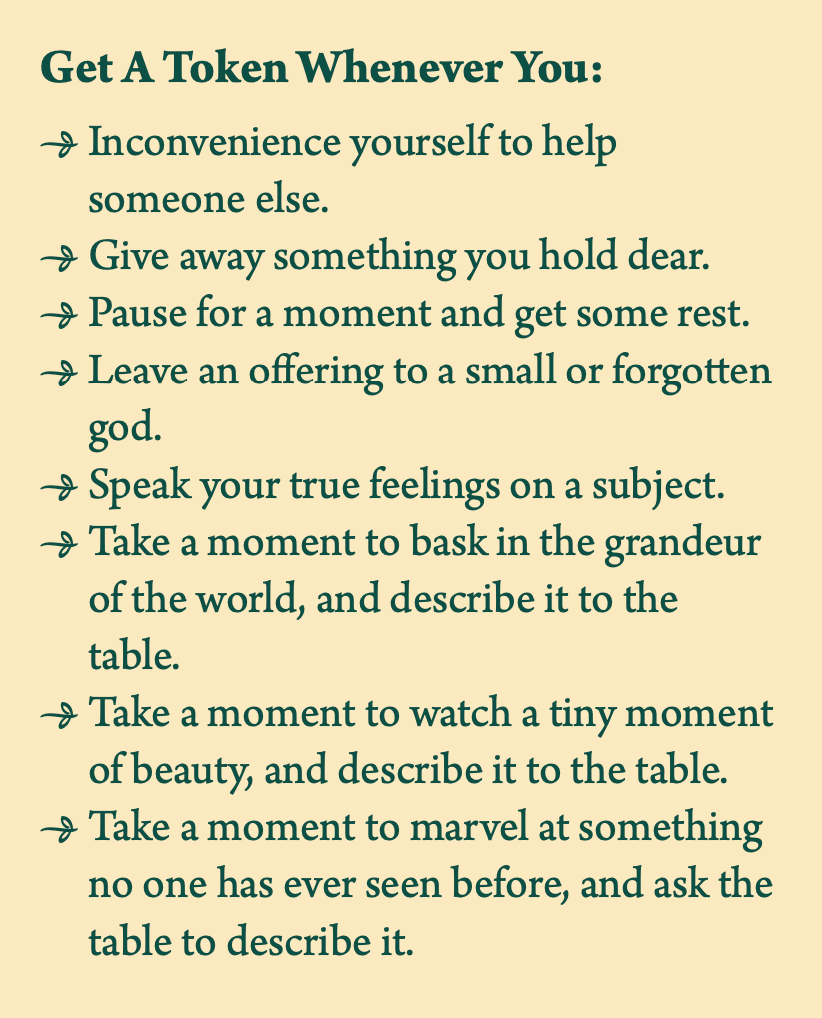

Meanwhile, in Wanderhome, there’s certain acts for which you receive a token, and those tokens can then be spent as a narrative currency to do other acts. These are explicitly rewarded behaviors, so again, while each one may not be appropriate for every moment or for every character, they are things that we all understand are on the table as “good behavior” in this social situation. If another player says, “And as I look up at the sky through the canopy of giant daisy petals, the sunlight is filtered through pink and orange and yellow, all dappled and warm,” I will understand that there is a moment of beauty here that we’re enjoying.

Between these two lists, you can see that there’s some overlap – like helping someone else – but not a lot. This isn’t to say that you COULDN’T sucker someone in a game of Wanderhome or give away something dear to you in a game of Apocalypse World. It only means that those are not really the expected modes of engagement, and will likely require additional explanation or context to get everyone else on the same page regarding what you’re going for. Just because something isn’t expected or typical doesn’t necessarily mean it’s wrong.

Both games DO have some “don’ts” that are spelled out clearly as well, though – often smaller things or finer points of play (I think this is partially because some basic etiquette is assumed like “don’t tell someone their idea sucks and they’re stupid for having it” and partially because saying “don’t do this” is a surefire way to make people want to do it, so it’s sometimes better not to even give them the idea. Don’ts are reserved for things we already see come up in play or that people will already lean towards doing without us bringing it up). Apocalypse World has notes like “don’t have your characters start the game as enemies, though they may become enemies later”; Wanderhome reminds you that “you are never going to solve a place’s problems”.

So let’s imagine a scenario where we, our imaginary game group, has just had a wonderfully successful Apocalypse World campaign. We all had a great time, we used the game’s built-in etiquette to engage in the situations presented in play, we absorbed the modes of behavior presented as expected and acceptable. Wow, what a great time we had. But we want to play something quite different now, because we’re a lovely varied bunch, and we decide to play Wanderhome for our next campaign.

If we just lift-and-shift all our same behaviors and all our same methods of engagement with play and story, from Apocalypse World to Wanderhome, we’re going to have a bad game of Wanderhome, even though they all just worked so well for AW! Even setting aside the tonal/genre specifics, the modes of play are also different in terms of their approaches to ambiguity, to having a GM role or not (optional in Wanderhome), to pacing, etc. And it’s compounded if half the group settles into Wanderhome-mode right away and half the group stays in Apocalypse-mode, or if only ONE person stays in Apocalypse-mode. Etiquette and game rules serve to get everyone on the same page, because both social situations and roleplaying games require a certain degree of harmoniousness between the participants.

It’s like thinking that I had a great time at my best friend’s bachelorette party on Friday night, behaving one specific way, so SURELY I will get equally good social results by behaving that exact same way at my grandma’s charity brunch on Saturday morning. Yes, I might say “could you please pass the champagne?” at both and get good results, but I probably should not ask a DJ to blast WAP for grandma and her church ladies, and I probably should not engage my friend in a long conversation about our respective health problems in the middle of the dance floor.

Because both etiquette and games are specific for a reason. Different situations require different behaviors, and sometimes different mindsets, in order for everyone to have the best possible time. An RPG book is like an etiquette manual in that it is telling you how best to engage for everyone to have a good time in THIS situation, and you cannot take for granted that “being on your best behavior” in one game looks the same in another.

(Sidebar: regarding a GM role mentioned earlier, RPGs as etiquette manuals is part of why I liken the facilitator role in most games to being a good party hostess. The hostess communicates the expectations for the event like “dinner served promptly at 6” or “it’s a pool party so bring a swimsuit if you want!” just like the facilitator communicates the expectations of the game like “this is a game about corny earnest golden age superheroes” or “this game has a really neat dice mechanic but it’s pretty crunchy, so we’ll go over it together a couple times while we get the hang of it”. And when there are breaches of etiquette or times where someone is clearly not on the same page, the hostess-facilitator is often, but not exclusively, the one to address that. I directly call the facilitator role in Dollhouse Drama “the hostess” because I want the game to feel like a tea party)

Closing Notes

I possibly achieved a new tier of “being a huge dweeb” this month. The Oxford Ancient Languages Society put on an entire production of the Ancient Greek tragedy Orestes… in the original Ancient Greek. The cast are speaking and singing in Ancient Greek. They’re wearing masks made in the style of Ancient Greek theatrical masks. And they put it all up for free on youtube with English subtitles. I watched the whole thing (it’s about 2 hours long) and it rules.

And then I thought, wouldn’t it be fun if I could log this on letterboxd? Like it was a regular movie? Of course it would. So I figured out the process for adding something to letterboxd and I created a page for it, so you can log it too when you definitely take my recommendation and watch it. Legitimately, I think it’s such an impressive piece of theatre and academia, and I love that it exists. I love that this 2500-year-old play can still be performed to the best of our understanding.

So anyway, back down to low culture, don’t forget to check out Gryphons & Gargoyles and also the latest Dollhouse Drama playset! Thanks for reading, catch you again next month!